Сказки просто так

Just So Stories

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Just So Stories, by Rudyard Kipling

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Just So Stories

Author: Rudyard Kipling

Release Date: December 22, 2008 [EBook #2781]

Last Updated: January 8, 2013

Produced by David Reed, and David Widger

JUST SO STORIES

By Rudyard Kipling

HOW THE WHALE GOT HIS THROAT

HOW THE CAMEL GOT HIS HUMP

HOW THE RHINOCEROS GOT HIS SKIN

HOW THE LEOPARD GOT HIS SPOTS

THE ELEPHANT’S CHILD

THE SING-SONG OF OLD MAN KANGAROO

THE BEGINNING OF THE ARMADILLOS

HOW THE FIRST LETTER WAS WRITTEN

HOW THE ALPHABET WAS MADE

THE CRAB THAT PLAYED WITH THE SEA

THE CAT THAT WALKED BY HIMSELF

THE BUTTERFLY THAT STAMPED

HOW THE WHALE GOT HIS THROAT

IN the sea, once upon a time, O my Best Beloved, there was a Whale, and he ate fishes. He ate the starfish and the garfish, and the crab and the dab, and the plaice and the dace, and the skate and his mate, and the mackereel and the pickereel, and the really truly twirly-whirly eel. All the fishes he could find in all the sea he ate with his mouth—so! Till at last there was only one small fish left in all the sea, and he was a small ‘Stute Fish, and he swam a little behind the Whale’s right ear, so as to be out of harm’s way. Then the Whale stood up on his tail and said, ‘I’m hungry.’ And the small ‘Stute Fish said in a small ‘stute voice, ‘Noble and generous Cetacean, have you ever tasted Man’

‘No,’ said the Whale. ‘What is it like?’

‘Nice,’ said the small ‘Stute Fish. ‘Nice but nubbly.’

‘Then fetch me some,’ said the Whale, and he made the sea froth up with his tail.

‘One at a time is enough,’ said the ‘Stute Fish. ‘If you swim to latitude Fifty North, longitude Forty West (that is magic), you will find, sitting on a raft, in the middle of the sea, with nothing on but a pair of blue canvas breeches, a pair of suspenders (you must not forget the suspenders, Best Beloved), and a jack-knife, one ship-wrecked Mariner, who, it is only fair to tell you, is a man of infinite-resource-and-sagacity.’

So the Whale swam and swam to latitude Fifty North, longitude Forty West, as fast as he could swim, and on a raft, in the middle of the sea, with nothing to wear except a pair of blue canvas breeches, a pair of suspenders (you must particularly remember the suspenders, Best Beloved), and a jack-knife, he found one single, solitary shipwrecked Mariner, trailing his toes in the water. (He had his mummy’s leave to paddle, or else he would never have done it, because he was a man of infinite-resource-and-sagacity.)

Редьярд Джозеф Киплинг

Just So Stories for Little Children / Просто сказки. Книга для чтения на английском языке

Предисловие

Вы знаете или изучаете английский язык? Вы хотите узнать ответы на вопросы, откуда у верблюда горб, а у слона – хобот; как появился алфавит и почему кошки гуляют сами по себе; что произойдет, если мотылек топнет ногой? И вас, конечно, интересует, как выглядело первое на Земле письмо и почему у носорога такая кожа? В таком случае это пособие для вас!

Сборник английского писателя Редьярда Киплинга, куда вошли сказки, рассказанные писателем его собственным детям, не только унесет вас в чудесный и удивительный мир прошлого и ответит вам и вашим детям на эти каверзные вопросы, но и поможет обогатить ваш лексический запас новыми словами и выражениями. В пособии объяснены некоторые трудности английской грамматики. В конце каждого рассказа предлагается выполнить ряд заданий, которые помогут запомнить новые встретившиеся в процессе чтения слова и выражения, а также лучше понять содержание рассказов.

Занимательные, знакомые с раннего детства сказки Киплинга создадут веселую атмосферу на занятиях по английскому языку и зарубежной литературе, а комментарии помогут с легкостью преодолеть трудности грамматики английского языка, возникающие при чтении неадаптированных текстов.

How the Whale Got His Throat

‘No’, said the Whale. ‘What is it like? [4] ’

This is the picture of the Whale swallowing [5] the Mariner with his infinite-resource-and-sagacity, and the raft and the jack-knife and his suspenders, which you must not forget. The buttony-things are the Mariner’s suspenders, and you can see the knife close by them. He is sitting on the raft, but it has tilted up sideways, so you don’t see much of it. The whity thing by the Mariner’s left hand is a piece of wood that he was trying to row the raft with when the Whale came along. The piece of wood is called the jaws-of-a-gaff. The Mariner left it outside when he went in. The Whale’s name was Smiler, and the Mariner was called Mr. Henry Albert Bivvens, A. B. The little ’Stute Fish is hiding under the Whale’s tummy, or else I would have drawn him. The reason that the sea looks so ooshy-skooshy is because the Whale is sucking it all into his mouth so as to suck in Mr. Henry Albert Bivvens and the raft and the jack-knife and the suspenders. You must never forget the suspenders.

‘Nice,’ said the small ‘Stute Fish. ‘Nice but nubbly.’

Then the Whale opened his mouth back and back and back till it nearly touched his tail, and he swallowed the shipwrecked Mariner, and the raft he was sitting on, and his blue canvas breeches, and the suspenders (which you must not forget), and the jack-knife. He swallowed them all down into his warm, dark, inside cupboards, and then he smacked his lips – so, and turned round three times on his tail.

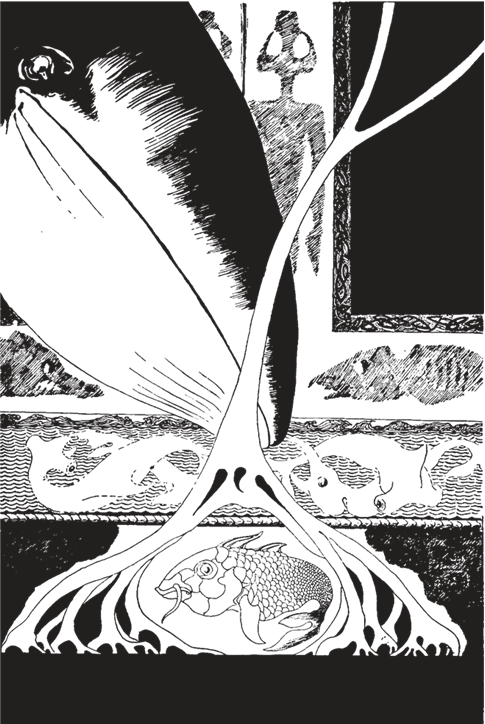

Here is the Whale looking for the little ’Stute Fish, who is hiding under the Door-sills of the Equator. The little ’Stute Fish’s name was Pingle. He is hiding among the roots of the big seaweed that grows in front of the Doors of the Equator. I have drawn the Doors of Equator. They are shut. They are always kept shut, because a door ought always to be kept shut. The ropy thing right across is the Equator itself; and the things that look like rocks are the two giants Moar and Koar, that keep the Equator in order. They drew the shadow-pictures on the Doors of the Equator, and they carved all those twisty fishes under the Doors. The beaky fish are called Beaked Dolphins, and the other fish with the queer heads are called Hammer-headed Sharks. The Whale never found the little ’Stute Fish till he got over his temper, and then they became good friends again.

But as soon as the Mariner, who was a man of infinite-resource-and-sagacity, found himself truly inside the Whale’s warm, dark, inside cupboards, he stumped and he jumped and he thumped and he bumped, and he pranced and he danced, and he banged and he clanged, and he hit and he bit, and he leaped and he creeped, and he prowled and he howled, and he hopped and he dropped, and he cried and he sighed, and he crawled and he bawled, and he stepped and he lepped, and he danced hornpipes [12] where he shouldn’t, and the Whale felt most unhappy indeed. (Have you forgotten the suspenders?)

‘Tell him to come out,’ said the ’Stute Fish.

So the Whale called down his own throat to the shipwrecked Mariner, ‘Come out and behave yourself. I’ve got the hiccoughs.’

‘Nay, nay!’ said the Mariner. ‘Not so, but far otherwise. Take me to my natal-shore and the white-cliffs-of-Albion, and I’ll think about it.’ And he began to dance more than ever.

‘You had better take him home,’ said the ’Stute Fish to the Whale. ‘I ought to have warned you [14] that he is a man of infinite-resource-and-sagacity.’

By means of a grating

have stopped your ating.’

The small ’Stute Fish went and hid himself in the mud under the Door-sills of the Equator. He was afraid that the Whale might be angry with him.

The Sailor took the jack-knife home. He was wearing the blue canvas breeches when he walked out on the shingle. The suspenders were left behind, you see, to tie the grating with; and that is the end of that tale.

Questions and tasks

1. How did the story begin? Why did the Whale want to find the Mariner?

2. Describe the Mariner.

3. What did the Mariner do after the Whale had swallowed him?

4. Why did the Whale have to take the Mariner home?

5. According to the story why were you not to forget the suspenders?

6. Retell the story.

How the Camel Got His Hump [22]

Now this is the next tale, and it tells how the Camel got his big hump.

In the beginning of years, when the world was so new-and-all, and the Animals were just beginning to work for Man, there was a Camel, and he lived in the middle of a Howling Desert because he did not want to work; and besides, he was a Howler himself. So he ate sticks and thorns and tamarisks and milkweed and prickles, most ’scruciating idler [23] ; and when anybody spoke to him he said ‘Humph! [24] ’ Just ‘Humph!’ and no more.

Presently the horse came to him on Monday morning, with a saddle on his back and a bit [25] in his mouth, and said, ‘Camel, O Camel, come out and trot [27] like the rest of us.’

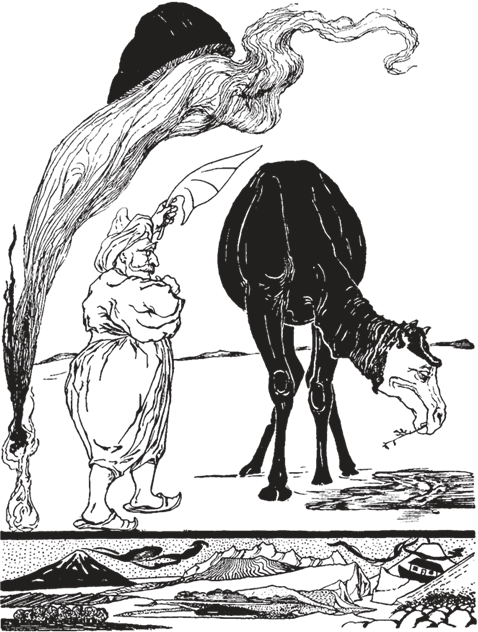

This is the picture of the Djinn making the beginnings of the Magic that brought the Humph to the Camel. First he drew a line in the air with his finger, and it became solid; and then he made a cloud, and then he made an egg – you can see them at the bottom of the picture – and then there was a magic pumpkin that turned into a big white flame. Then the Djinn took his magic fan and fanned that flame till that flame turned into a Magic by itself. It was a good Magic and a very kind Magic really, though it had to give the Camel a Humph because the Camel was lazy. The Djinn in charge of [26] all Deserts was one of the nicest of the Djinns, so he would never do anything really unkind.

‘Humph!’ said the Camel; and the Horse went away and told the Man.

Presently the Dog came to him, with a stick in his mouth, and said, ‘Camel, O Camel, come and fetch and carry like the rest of us.’

‘Humph!’ said the Camel; and the Dog went away and told the Man.

Presently the Ox came to him, with the yoke on his neck, and said, ‘Camel, O Camel, come and plough [28] like the rest of us.’

‘Humph!’ said the Camel; and the Ox went away and told the Man.

At the end of the day the Man called the Horse and the Dog and the Ox together, and said, ‘Three, O Three, I’m very sorry for you (with the world so new-and-all); but that Humph-thing in the Desert can’t work, or he would have been here by now, so I am going to leave him alone, and you must work double-time to make up for it.’

Presently there came along the Djinn in charge of All Deserts, rolling in a cloud of dust (Djinns always travel that way because it is Magic), and he stopped to palaver and pow-wow with the Three.

‘Djinn of All Deserts,’ said the Horse, ‘is it right for any one to be idle, with the world so new-and-all?’

‘Certainly not’, said the Djinn.

Here is the picture of the Djinn in charge of All Deserts guiding the Magic with the magic fan. The Camel is eating a twig of acacia [31] , and he has just finished saying ‘Humph!’ once too often (the Djinn told him he would), and so the Humph is coming. The long towelly thing growing out of the thing like an onion is the Magic, and you can see the Humph on its shoulder. The Humph fits on the flat part of the Camel’s back. The Camel is too busy looking at his own beautiful self in the pool of water to know what is going to happen to him.

Underneath the truly picture is a picture of the World-so-new-and-all. There are two smoky volcanoes in it, some other mountains and some stones and a lake and a black island and a twisty river and a lot of other things, as well as a Noah’s Ark. I couldn’t draw all the deserts that the Djinn was in charge of, so I only drew one, but it is a most deserty desert.

‘Whew!’ said the Djinn, whistling, ‘that’s my Camel, for all the gold in Arabia! What does he say about it?’

‘He says “Humph!”’said the Dog; ‘and he won’t fetch and carry.’

‘Does he say anything else?’

‘Only “Humph!”; and he won’t plough,’ said the Ox.

‘Very good,’ said the Djinn. ‘I’ll humph him if you will kindly wait a minute.’

The Djinn rolled himself up in his dust-cloak, and took a bearing across the desert, and found the Camel most ’scruciatingly idler, looking at his own reflection in a pool of water.

‘My long and bubbling friend,’ said the Djinn, ‘what’s this I hear of your doing no work, with the world so new-and-all?’

‘Humph!’ said the Camel.

The Djinn sat down, with his chin in his hand, and began to think a Great Magic, while the Camel looked at his own reflection in the pool of water.

‘You’ve given the Three extra work ever since Monday morning, all on account of your ’scruciating idleness,’ said the Djinn; and he went on thinking Magics, with his chin in his hand.

‘Humph!’ said the Camel.

‘Do you see that?’ said the Djinn. ‘That’s your very own humph that you’ve brought upon your very own self by not working. Today is Thursday, and you’ve done no work since Monday, when the work began. Now you are going to work.’

‘How can I,’ said the Camel, ‘with this humph on my back?’

‘That’s made a-purpose,’ said the Djinn, ‘all because you missed those three days. You will be able to work now for three days without eating, because you can live on your humph; and don’t you ever say I never did anything for you. Come out of the Desert and go to the Three, and behave. Humph yourself!’

And the Camel humphed himself, humph and all, and went away to join the Three. And from that day to this the Camel always wears a humph (we call it ‘hump’ now, not to hurt his feelings; but he has never yet caught up with the three days [37] that he missed at the beginning of the world, and he has never yet learned how to behave.

The Camel’s hump is an ugly [38] lump

Which well you may see at the Zoo;

But uglier yet is the hump we get

From having too little to do.

Kiddies and grown-ups too-oo-oo,

If we haven’t enough to do-oo-oo,

We get the hump —

Cameelious hump —

The hump that is black and blue!

We climb out of bed with frowzy [39] head

And a snarly-yarly voice.

We shiver and scowl and we grunt and we growl [40]

At our bath and our boots and our toys;

And there ought to be a corner for me

(And I know there is one for you)

When we get the hump —

Cameelious hump —

The hump that is black and blue!

The cure for this ill is not to sit still,

Or frowst with a book by the fire;

But to take a large hoe and a shovel also,

And dig till you gently perspire [41] ;

And then you will find that the sun and the wind,

And the Djinn of the Garden too,

Have lifted the hump —

The horrible hump —

The hump that is black and blue!

I get it as well as you-oo-oo —

If I haven’t enough to do-oo-oo!

We all get hump —

Cameelious hump —

Kiddies and grown-ups too!

Questions and tasks

1. What animals came to the Camel? What did they offer to the Camel and what was the answer?

2. Why were the animals very angry after the

Man had talked to them?

3. Retell the story from the moment the Djinn appeared in it.

4. What did the Djinn do for making the Camel work?

5. What ‘advantages’ did the hump on the back give to the Camel?

6. Retell the story.

How the Rhinoceros [42] Gt His Skin

‘Them that takes cakes

Which the Parsee-man bakes

Makes dreadful mistakes.’

This is the picture of the Parsee beginning to eat his cake on the Uninhabited Island in the Red Sea on a very hot day; and of the Rhinoceros coming down from the Altogether Uninhabited Interior, which, as you can truthfully see, is all rocky. The Rhinoceros’s skin is quite smooth and the three buttons that button it up [49] are underneath, so you can’t see them. The squiggly things on the Parsee’s hat are the rays of the sun reflected in more-than-oriental splendour, because if I had drawn real rays they would have filled up all the picture. The cake has currants [50] in it; and the wheel-thing lying on the sand in front belonged to one of Pharaoh’s chariots when he tried to cross the Red Sea. The Parsee found it, and kept it to play with. The Parsee’s name was Pestonjee Bomonjee, and the Rhinoceros was called Strorks, because he breathed through his mouth instead of his nose. I wouldn’t ask anything about the cooking-stove if I were you.

This is the Parsee Pestonjee Bomonjee sitting in his palm-tree and watching the Rhinoceros Strorks bathing near the beach of the Altogether Uninhabited Island after Strorks had taken off his skin. The Parsee has rubbed the cake-crumbs into the skin, and he is smiling to think how they will tickle Strorks when Srorks puts it on again. The skin is just under the rocks below the palm-tree in a cool place; that is why you can’t see it. The Parsee is wearing a new more-than-oriental-splendour hat of the sort that Parsees wear; and he has a knife in his hand to cut his name on palm-tree. The black things on the islands out at sea are bits of ships that got wrecked going down the Red Sea; but all the passengers were saved and went home. The black thing in the water close to the shore is not a wreck at all. It is Strorks the Rhinoceros bathing without his skin. He was just as black underneath [56] his skin as he was outside. I wouldn’t ask anything about the cooking-stove if I were you.

But the Parsee came down from his palm-tree, wearing his hat, from which the rays of the sun were reflected in more-than-oriental splendour, packed up his cooking-stove, and went away in the direction of Orotavo, Amygdala, the Upland Meadows of Antananarivo, and the Marshes of Sonaput.

This Uninhabited Island

Is off Cape [61] Gardafui,

By the Beaches of Socotra

And the Pink Arabian Sea:

But it’s hot – too hot from Suez

For the likes of you and me

Ever to go

In a P. & O.

And call on the Cake-Parsee.

Just so Stories / Сказки Аудио

Посоветуйте книгу друзьям! Друзьям – скидка 10%, вам – рубли

Эта и ещё 2 книги за 299 ₽

Если вы изучаете английский язык или свободно на нем говорите, у вас есть замечательная возможность прослушать на языке оригинала знаменитые «Сказки» Киплинга о том, как животные стали такими, какими мы их знаем, а затем проверить свое понимание произведения, прослушав русский перевод. Текст адаптирован и соответствует уровню Рre-Intermediate/Intermediate.

Аудиокнига на английском и русском языках.

Английскую версию читает Joseph Samuel Bagley

1. Как верблюд получил свой горб

2. Как кит получил свою глотку

3. Как носорог получил свою шкуру

4. Кот, который гулял сам по себе

5. Мотылек, который топнул

6. Песенка Старины Кенгуру

С этой книгой слушают

Отзывы 4

Английский чтец читает очень хорошо – четко, с правильным британским произношением, не слишком быстро. Русский показался слишком медленным. Аудиокнига, безусловно, пригодится как изучающим английский язык, так и преподавателям: небольшой хронометраж позволяет использовать сказки на уроках для тренировки аудирования. Однако для учеников с самым начальным уровнем она не совсем подходит, хоть сказки и адресованы детям: текст все-таки не адаптированный. У Киплинга очень поэтичный и образный язык. Во многом его сказки – это стихотворения в прозе. Поэтому сравнить две версии может быть интересно даже практикующим переводчикам: узнать, как передана игра слов, оценить выбранное решение и попытаться придумать свое, улучшенное.

Английский чтец читает очень хорошо – четко, с правильным британским произношением, не слишком быстро. Русский показался слишком медленным. Аудиокнига, безусловно, пригодится как изучающим английский язык, так и преподавателям: небольшой хронометраж позволяет использовать сказки на уроках для тренировки аудирования. Однако для учеников с самым начальным уровнем она не совсем подходит, хоть сказки и адресованы детям: текст все-таки не адаптированный. У Киплинга очень поэтичный и образный язык. Во многом его сказки – это стихотворения в прозе. Поэтому сравнить две версии может быть интересно даже практикующим переводчикам: узнать, как передана игра слов, оценить выбранное решение и попытаться придумать свое, улучшенное.

Прекрасная книга. Люблю «Сказки» Киплинга ибо в них можно почувствовать не только фантазию, но и отссылки к настоящему миру. Плюс книга на английском, я люблю слушать литературу в оригинале.